Undated (1967) New Zealand Bahamas Mule

In 1967 was it a careless mistake by a Royal Mint worker that saw the birth of a rare and now famous mule coin? Seen above is one of these prized pieces with two sides that were never intended to be used together. A copper 2c piece struck by the Royal Mint for New Zealand bears the undated obverse of a Bahamas 5 cent (an obverse which should have been struck on a copper nickel blank). The reverse is the New Zealand kowhai blossom designed by Reginald George James Berry (known as James Berry) who designed the reverses of all the new decimal coins of New Zealand, his initials JB appear on the coin. The obverse is the Arnold Machin portrait of Queen Elizabeth II with the country of Bahama Islands instead of New Zealand. The date on a New Zealand coin should appear below the portrait but does not appear on the Bahamas obverse leaving the coin undated.

A full production run (between 65,000 and 100,000) of these error coins was mistakenly manufactured by the Royal Mint in London when preparing New Zealand coins for their changoever to decimal currency in 1967. The error went unnoticed and the coins were packed and sent to Wellington, New Zealand to be distributed at decimal changeover on 10th July 1967. Within hours of the new currency circulating the accidental pairing had been discovered.

It was all over the news and the media had a field day with headlines such as “Freak 2c coin of no legal value” and “Mint bungle could make 2c coin worth $200”. Mr John Searle of the New Zealand Decimal Currency Board asked the New Zealand High Commissioner in London to speak with the Royal Mint and explain as there could be as many as 100,000 coins circulating that weren’t true legal tender. A full inquiry would take place and the Royal Mint would supply 100,000 replacement coins to the New Zealand government at no cost. The day after New Zealand C-Day 11 July 1967 New Zealand Minister of Finance Robert Muldoon said in a press statement:

“The resulting defective coins are not legal tender in New Zealand but the Government will exchange them for genuine New Zealand coins of the same face value.”

Who would take up such an offer! The public and collectors requested to buy the coins. Since the Royal Mint were replacing the coins should they be offered for sale at financial gain to the Government? The Bahamas die that was wrongly used belonged to another government, would it be proper to use this misuse for financial gain? At this point a 2 cent piece that cost NZ treasury essentially nothing as the coins had been replaced were fetching up to $50 each.

New Zealand 1967 2 cent (top) and Bahama Islands 1966 5 cent (bottom) Note: no Bahama Island 5c were minted dated 1967

By August 4th 1967 New Zealand Treasury had decided what to do. Finance Minister Robert Muldoon gave a mule to 78 members of parliament. A mule was also given to the NZ Governor General Bernard Fergusson and Wellington born Bahama Islands Governor Ralph Grey. New Zealand treasury also gifted mules to members of Numismatic societies and clubs with conditions that they promised not to sell the gifted coins.

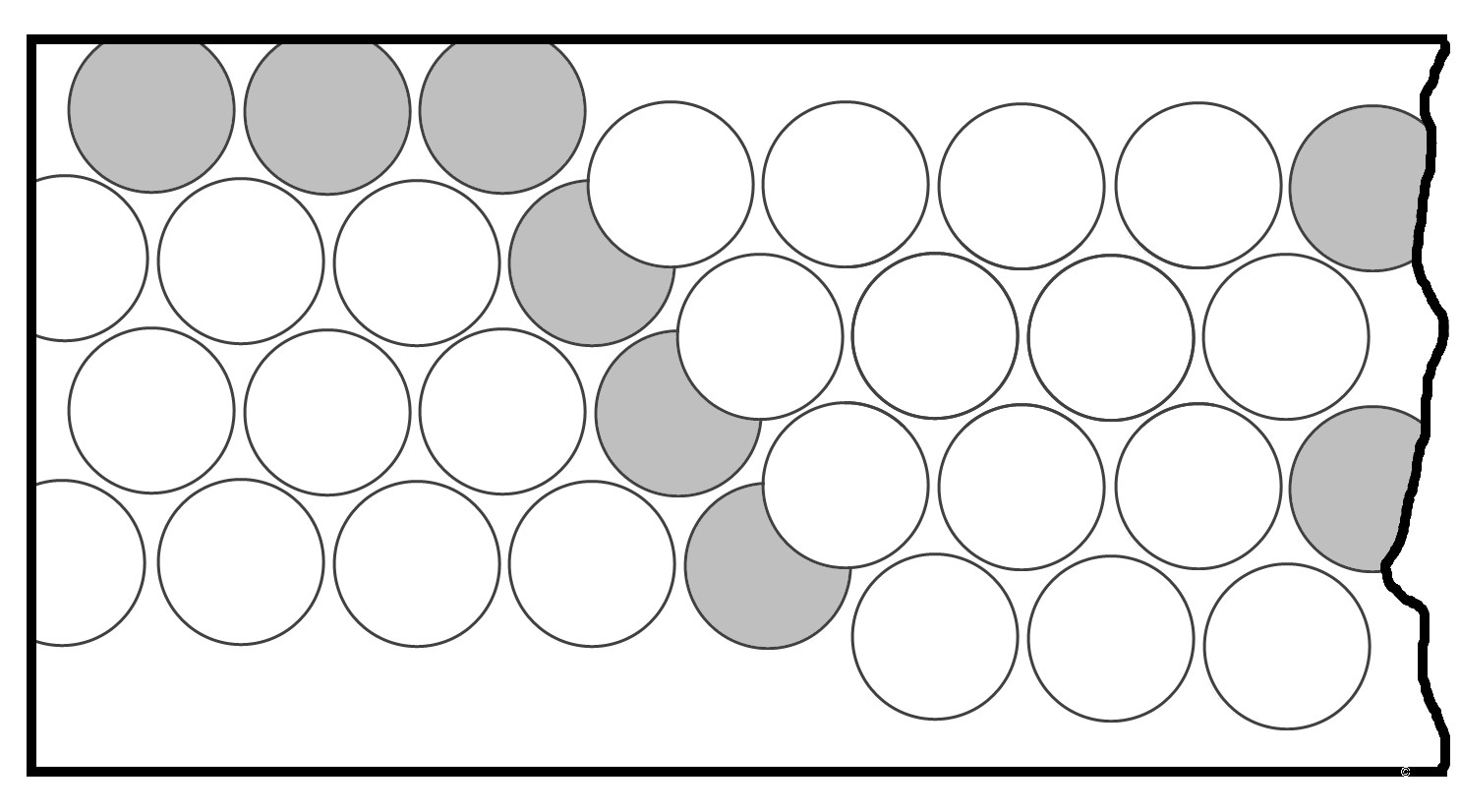

A Royal Mint enquiry into the incident was undertaken and found most defective coins were contained in batch 73 and were minted on the night shift of Wed 18th January or the day shift of Thurs 19th January 1967 where 20 people worked. There was a maximum of 9 presses and 34 dies in use during this time. The Royal Mint were NOT minting any Bahama Island coins during that week but Bahama Island coin dies were held in the die stronghold. Checks of unused dies failed to shed light on how this mistake occurred. Without further evidence it is believed to be the result of only one wrong die. Without evidence of the use of more than one die the only conclusion is that not more than 150,000 of these coins could exist. The report suggests the New Zealand authorities check the surrounding bags 72 and 74 for suspect coins also. Because nine presses were in use the Royal Mint concludes 100,000 defective coins could be included in up to 900,000 sent to New Zealand. The Royal Mint apologized, replaced the coins and the covered the cost of the recovery of the mule coins.

The Royal Mint at Tower Hill in London had been minting coins since (circa) 1810 and was under tremendous load at the time minting coins for many different countries and ex-colonies some of which were moving to decimalisation. This included Australia when London minted new 5c, 10c and 20c for Australia’s change to decimal currency in 1966 and they were preparing for Britains own decimalisation in 1971. Any mistakes or bad press could lead countries away from using the Royal Mint to strike their coins. Their equipment was becoming tired and little did they know a new Mint was being planned. The new Mint in Llantrisant was announced in April 1967 and work started in August. There was also shortage of staff and it has been suggested that the making of the New Zealand Bahamas mule was a deliberate industrial protest by workers and not a simple accident. They did manage through strong coincidence to strike these coins, send them away and release them into circulation without the error being detected.

600 Royal Mint workers were involved in an unofficial strike in the coinage room on Friday January 6th 1967, just 2 weeks before these mules were made. However John Hasting James (Deputy Mint Master 1957 to 1970) explicitly stated it was the view of Mint management that this was not a deliberate act from a disaffected Mint employee. Later, in August 1967, another letter stated after Deputy Mint Master John James visited the factory at the beginning of January he found supervision to be substandard and the factory Superintendent was warned severely. A mistake should have been no surprise however in theory the die checking procedures should have prevented such an event. Because of the length of time between manufacture and detection it was impossible to identify the exact person or persons responsible (individual press records were destroyed once numbers tallied to avoid volumes of paper). If it was done on purpose then it’s likely die records were altered by those responsible. No disciplinary action was taken against anyone. From August 1967 new procedures were put in place at the Royal Mint to stop this from happening again.

A full production run (the number of coins struck between die changes) meant that it was possible that 100,000 mule coins were struck. Treasury traced the mules to 2 bank sources and identified boxes, batch numbers and bag numbers and went through those 600,000 coins by hand finding 60,000 mules that were later meted down. This has resulted in an estimated 6,000-12,000 coins in collectors hands.