Above you can see what appears to be, on first glance, a well worn Australian shilling from 1928. In fact, what you can see above is a well worn silver disc purporting to be a 1928 shilling. It is a cleverly executed contemporary forgery struck in good silver in China and then imported into Australia for circulation in the early 1930’s. How, I hear you ask, can someone make a profit striking a coin in silver? Well in the 1930’s a shilling contained only about 2 1/2 pennies worth of silver, leaving 9 1/2 pence to cover manufacturing, shipping and profit [11]. You can easily see how a profit could be turned.

These 1928 shilling forgeries are not as well known as the so-called “Manders and Twible” forgeries of the same era, yet in their own way they are just as interesting and equally well made. In 1931 and 1932 banks in several major Australian state capitals became concerned at the number of 1928 shillings in rolls and bags that were being cashed in for notes. The police were called in and upon examination the coins were found to be good silver (in fact some were higher purity than sterling), and probably machine struck.

While analysis of the forgeries was carried out in 1932 detective work was undertaken by Detective-Inspector Prior of the Sydney CIB. Prior worked with Australian Treasury officials and gained cooperation of Commonwealth Bank managers who would report excessive deposits of silver shillings. Soon enough a Sydney branch reported a well dressed Chinese man depositing packaged shillings and low denomination notes to be exchanged for high value notes. This man, it was found out, was well spoken, held international qualifications in Commerce, and was a local carpet and fabric merchant who went by the name of Kwong Khi Tseng. In fact he was held in such esteem locally and internationally that police were inclined to dismiss him as a suspect.

However, in the interest of thoroughness Detective Prior appointed Frank Fahy, Australia’s first official undercover policeman to tail Tseng. Fahy followed Tseng and saw him deposit further numbers of shillings and notes into various banks around Sydney and identified two other Chinese who were depositing similar notes and coins into different banks. Within two weeks Fahy was convinced the three men were the source of the spurious coins as “the volume of shillings he had seen them convert was far in excess of the normal amount in a warehouse business like theirs”. However, Fahy was also sure that the coins were not being made locally but had no real idea where they were being sourced. His answer came a few weeks later when he followed the three men to a ship that had just arrived from China. One of the men boarded the ship and left just a few minutes later bearing a heavy case. The case was presented to Customs and passed without question. Fahy spoke to the Customs officer later and was told that the Chinese men were well known and often brought large amounts of silver currency into Australia and out of Australia.

Shortly thereafter the fabric and carpet warehouse was raided where “hundreds of pounds worth of shilling pieces” were found. One of the suspects was arrested simultaneously at the Union Bank in George St, Sydney where he was changing 20 pounds worth of notes and shillings. Charges were soon laid against the Chinese merchant and his two accomplices. Two of the three were found guilty and all three were promptly deported from Australia and warned that they, and their families, were no longer welcome in Australia.

In 1946 in the Sydney Morning Herald, a former government analyst who had been involved with the case in the 1930’s was interviewed by a staff reporter. The analyst, named Mr. Walton said [1]:

The matter was brought to the attention of the analytical branch; it was discovered that the coins deviated little in weight from the real article, their alloy approximated that of genuine Australian currency, and they had obviously been stamped out by a very efficient machine

Walton went on to say in a later edition of the paper:

The coins were all shillings dated 1928 and it is believed they minted in a town called Swatow in China; Three Chinese were charged with uttering, and it was proved one came from that town.

The author of ‘The Fake 1928 Shillings’ (1984) says that Swatow (in Kwangtung province) was also rumoured to be the source of other similar sized silver counterfeits such as 1922 Netherlands 1/2 guilders, US 1/4 dollars, and French francs.

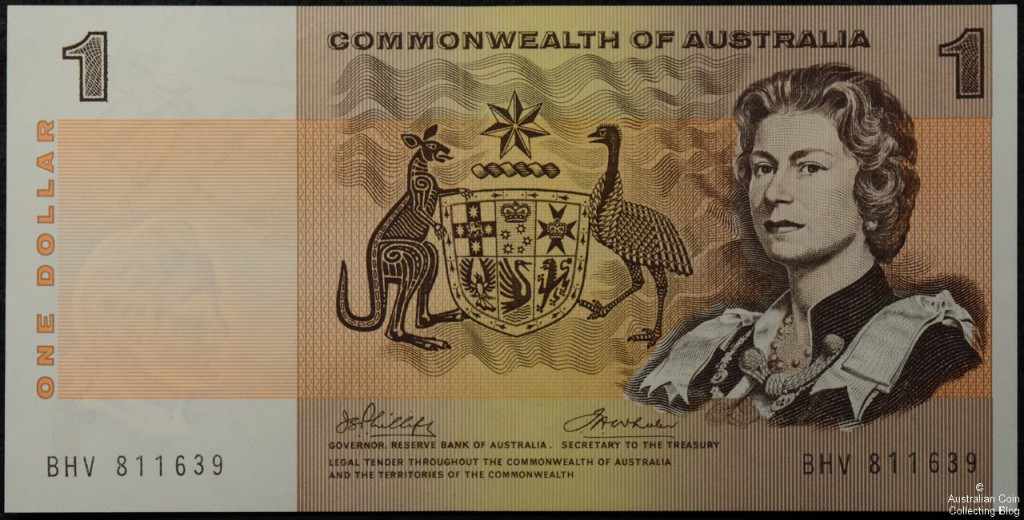

Counterfeit 1928 shilling (left), genuine 1928 shilling (right)

Images courtesy of The Sandpit

Update 13 July 2015

On a recent coin buying trip we were lucky enough to find another of these counterfeit 1928 shillings in a dealer’s stock book. To our surprise the coin is the same coin as shown in the images above (those courtesy of The Sandpit). The owner of that site last saw the coin several years ago (he did not own it), and somehow the fates have worked to put the very same coin into our hands. Here’s an updated image of that coin:

It’s interesting to note that this very same coin is found imaged in the August 2009 edition the Australasian Coin & Banknote Magazine in an article entitled “The 1928 Dodgy Deener” by Ian McConnelly.

Update 8 December 2016

Almost a year and a half after we last found one of these forgeries we came across another one at a coin show in Adelaide in the stock books of Victorian coin dealer Steele Waterman. We paid $20 for the coin, which honestly is probably a fair value for something that is surprisingly difficult to find.

Interestingly a friend of ours also found one in the last few months at a coin show in Victoria.

Update 11 October 2022

It’s a delight to re-visit this article after several years. The fantastic website Trove has suggested some more information regarding the counterfeit 1928 shillings. Firstly, the three Chinese gents who deposited their fake shillings around banks in Sydney appear to have mixed them in with genuine shillings in an attempt to mis-lead bank tellers. There was a well developed “system adopted by the defendants to mix spurious shillings with genuine ones” [9].

The second point of interest is that several newspaper articles suggest that not only 1928 shillings were counterfeit, but also 1925 shillings. The The Labor Daily says that “the majority of the bad coins bear 1928 date. Others are marked 1925.” [10] So could we have another counterfeit shilling to look out for? It certainly could be the case!

Possible Source of Silver?

It’s interesting to postulate about the source and type of silver used to make these counterfeits. Gangland Sydney (2011) gives one possible hint when discussing the case [6]:

The coins, all dated 1928, contained up to 3 percent less silver than a genuine Australian shilling.

Given that a real Australian shilling of the period is sterling silver (92.5%) if we subtract 3% from this we arrive a 89.5% which is remarkably close to the silver content of coins that would have been found in China at the time. 89% and 90% happen to be the most common silver percentages used for Chinese silver dollars of the period while 90% was the silver percentage of US silver coins. It’s also interesting to note that 90.3% was the most common silver percentage of Mexican silver crowns that were commonly used for trade in China in the 19th century and the early part of the 20th. It’s not hard to imagine that the forgers in Swatow sourced their silver by collecting up all the silver dollar sized coins they could at silver value and melting them down to produce the blanks for their dud Aussie shillings!

How to Detect a Counterfeit 1928 Shilling

Above you can see an image comparing a counterfeit and a genuine 1928 shilling with areas of interest circled in red (click on the image to enlarge). Determining if a 1928 shilling is one of these counterfeit silver coins is relatively simple through examination of the reverse. First examine the standing leg of the emu. On the counterfeit about one third down the emu’s leg there’s a small die chip just to the right of the leg. You can see this feature circled on the image above. The second difference is in the surface of the grass at the base of the coat of arms. On the genuine coin the grass is smooth and shows as ‘blades of grass’. While on the counterfeit the grass is hazy and is represented as a series of spots and blobs and lines.

Scarcity of the Counterfeit 1928 Silver Shillings

These silver forgeries are very scarce. Much more so than the silver “Manders and Twible” forgeries, with perhaps the exception of the 1931 counterfeit florin struck by the pair of well known forgers. The authors of this article have only ever sighted one two three examples (all imaged in this article). Another much more experienced collector we know has been looking for these coins for 15 years and has only seen about 6 or 7 examples in that time. Ian McConnelly, a well known Australian variety collector and author hadn’t managed to find one and in our time looking for (several) years we’ve found three. Their scarcity and interesting back story makes them quite interesting to collectors, especially those who are putting together collections of counterfeit pre-decimal coins.

It’s worth a quick look at what the references say about how many of the fake 1928 deeners were supposedly made and how this compares with the actual mintage of real 1928 shillings. The real 1928 shilling has a fairly low mintage of just under 700,000 coins. Sources suggest that as much as £9000 [10] worth or as little as £470 [9] worth of the fake coins were released. This puts the number of fakes between about 10,000 (1 in 70 real coins) and 180,000 (1 in 4 real coins). Given these suggested find rates why have there been less than 10 actual countefeits found in the thousand or more 1928 shillings examined since the authors started looking for them? There are some possible explanations:

1. The £9000 figure is simply wrong. £9000 in shilling is over 1,000 kilograms of coins which would have been extraordinarily difficult to get into the country.

2. If the £9000 figure is correct only a small portion would have been seized by authorities as the Chinese gentlemen in question had been depositing them for at least six weeks before banks reported their suspicions to police. [10] So why are so few found? Perhaps the telltale die chip on the emu’s leg only happened late in the counterfeit die production run. What’s the upshot of this? If we are to believe the £9000 figure then as many as 1 in 5 1928 shillings found now are fakes but essentially undetectable.

3. In our 11 October 2022 update we mentioned the possibility that not all the fakes were dated 1928, but also 1925. Perhaps the £9000 figure also includes many tens of thousands of 1925 counterfeits that are similarly undetected.

4. It seems very likely that the £9000 is inaccurate. The Truth in September 1932 [11] reports that £470 had been distributed by the Chinese men in five weeks. Disposing of £9000 at the same rate would have taken almost two years! It seems incredibly unlikely that the activity would have gone unnoticed for so long.

5. If we assume the £9000 figure is wrong and the real number of fakes is as little as £470 then this may explain the relative scarcity of the fakes. Even then with a suggested find rate of 1 in 70 real coins we should find the fakes more often. So why don’t we? Perhaps the police and banks gathered up the vast majority of counterfeits and melted them. Or again, perhaps the tell-tale die chip is only present on some of the counterfeit 1928 coins.

Update 17 December 2023

Once again it’s a pleasure to revisit this article with further research. Firstly we note with some interest the discrepancies in the references with regards to the silver content of the dodgy 1928 shillings. The Sydney Morning Herald[9], reporting on proceedings in the Central Police Court states that the (coins) “had been assayed and it had been disclosed that they contained 10 percent less silver than Australian coins”. Compare that with the three percent shortfall suggested by Gangland Sydney (2011) as we’ve stated earlier in this article. Finally, former NSW government analyst Sidney G. Walton stated in the 1946 article ‘Analyst Studies Crime, Food, Beer, Lipstick’ that “their alloy approximated that of genuine Australian currency” [1]. Clearly there is no consistency in the references as to the silver content of the fake 1928 shillings. Soon we will publish a detailed XRF analysis of the three counterfeits we have on hand along with a comparison with other genuine shillings of the same era and see how this stacks up against the references.

References

[1] ‘Analyst Studies Crime, Food, Beer, Lipstick’, Sydney Morning Herald (31 January 1946), p. 2.

[2] Dean, John 1965, ‘The 1965 Australian Coin Varieties Catalogue’, Melbourne: The Hawthorn Press

[3] Fleming, Owen 1984, ‘The fake 1928 shillings’, Australian Coin Review, August Vol 21 No. 2, pp11-17

[4] Kelly, Vince 1954, ‘The Shadow – the Amazing Exploits of Frank Fahy’

[5] McConnelly, Ian 2009, ‘The 1928 Dodgy Deener’, The Australasian Coin & Banknote Magazine, August Vol 12 No. 7, pp28-29

[6] Morton, James & Lobez, Susanna 2011, ‘Gangland Sydney’, Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing, pp29

[7] Saxton, Jon 2004, ‘Fake Florins Shonky Shillings and Spurious Sixpences’, The Australasian Coin and Banknote Magazine, July Vol 7 No. 6, pp24-29

[8] Saxton, Jon (Date Unknown) The 1926-1931 florin forgeries, Online, Available: http://www.triton.vg/Manders.html Retrieved 18 January 2015

[9] ‘Counterfeit Coins’, Sydney Morning Herald (9 September 1932), p. 9.

[10] ‘Part of World White Gang, So Police Claim’, The Labor Daily (17 August 1932), p. 6.

[11] ‘Spurious Shillings’, The West Australian (9 September 1932), p. 19.

[12] ‘Influential Chinese on Uttering Charge’, Truth (11 September 1932), p. 8.