A version of this article was originally published in the May 2024 edition of the free online coin mazazine, Independent Coin News.

Figure 1 The Milk Tin

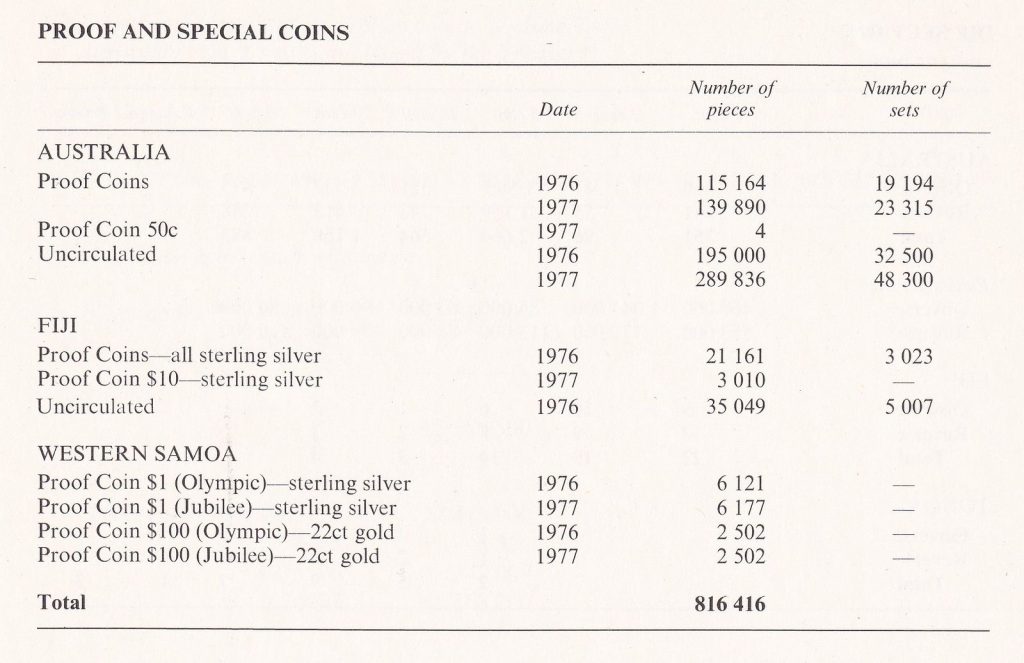

At about 3pm on a Wednesday in mid-February 2024, a young man walked into our coin shop holding a small canvas bag in one hand and a large silver tin with a red label in the other. As he placed them on the counter where we handle all of our purchasing, the bag made a distinctive clinking sound, a sound we’ve heard many times before, that of silver coins moving gently against each other. The tin, perhaps 35cm high and 20cm in diameter, had a bold red and cream logo that read “VI-LACTOGEN FOR INFANTS” (Figure 1).

As always, we asked our customer where he’d come across his items. He said, “This is just a small part of what I found in a house that my company owned and was demolishing”. He went on, “I’ve had them for a couple of years and finally opened some of the tins and found some coins in them,. I’ve brought them in to sell but I’m not expecting much”. Knowing there were coins in the bag we asked, “What’s in the tin?”

If you look closely at the image of the tin in Figure 1, you’ll see the remnants of solder that sealed it closed. The customer broke the solder, lifted off the lid, and inside we saw a stack of hundreds of banknotes! A quick flick through the stack revealed many Australian ten shilling banknotes, all with the distinctive orange colour of those issued under King George VI. Concealing our excitement we asked if we could also look in the canvas bag and when gaining permission we found 240 circulated 1942 florins. They were minted at both the Royal Mint branch in Melbourne and the US Mint branch in San Francisco.

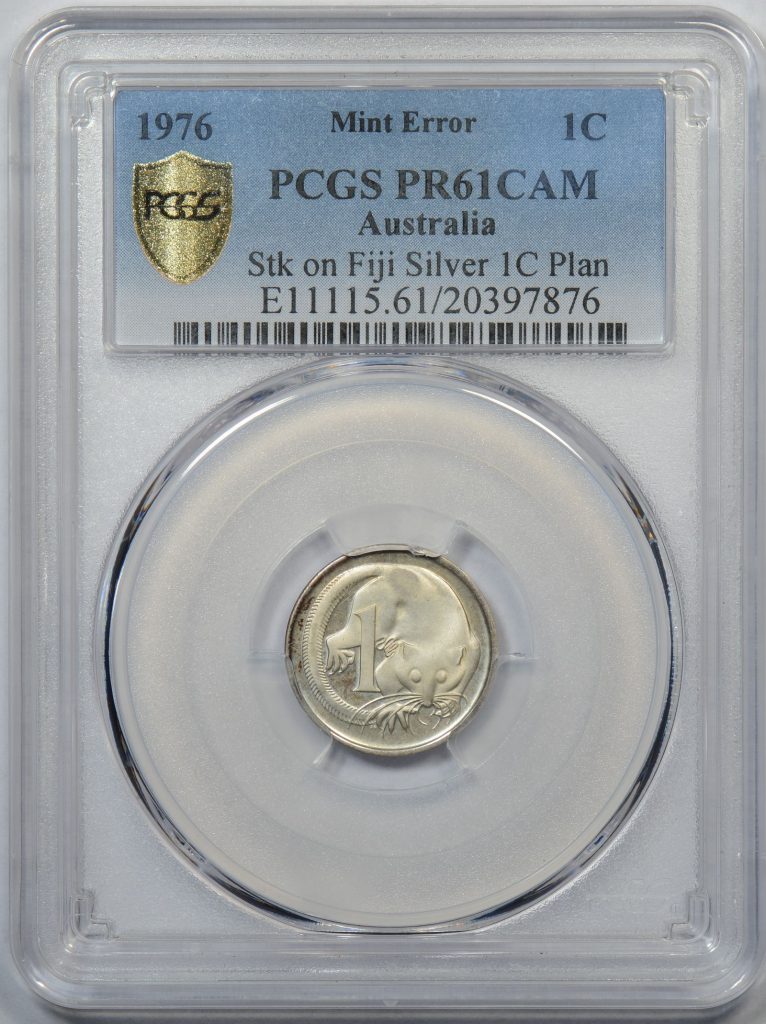

“So do you think I might get a few hundred dollars?” asked the customer. “Uh yes,” we replied, “We think you’ll get a fair bit more than that mate”. Needless to say, after some negotiation, we purchased the banknotes in the tin, the coins in the bag, and many kilos of other coins that were part of this hoard. After such a large purchase we were left somewhat stunned, and our customer was planning a rather unexpected but elaborate European holiday! It’s not the first time we’ve bought a group of banknotes found in a house undergoing demolition. To put The Milk Tin Hoard into context, those other hoards had 20, or even 30 notes but certainly not the 219 ten bob notes contained in the old baby formula tin (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The 219 ten shilling notes comprising the Milk Tin Hoard

Note Hoard Composition and Condition

Once we’d taken ownership of the notes, we took them out of the tin and sorted them by signatories and grades. Table 1 shows a breakdown of the notes in the hoard, using Renniks3 reference numbers:

| Signatories |

First Issued |

Ref. |

Count |

| Sheehan / McFarlane |

1939 |

R-12 |

8 |

| Armitage / McFarlane |

1942 |

R-13 |

137 |

| Coombs / Watt |

1949 |

R-14 |

54 |

| Coombs / Wilson |

1952 |

R-15 |

20 |

| Total: |

219 |

Table 1 – Hoard Composition by Signatories

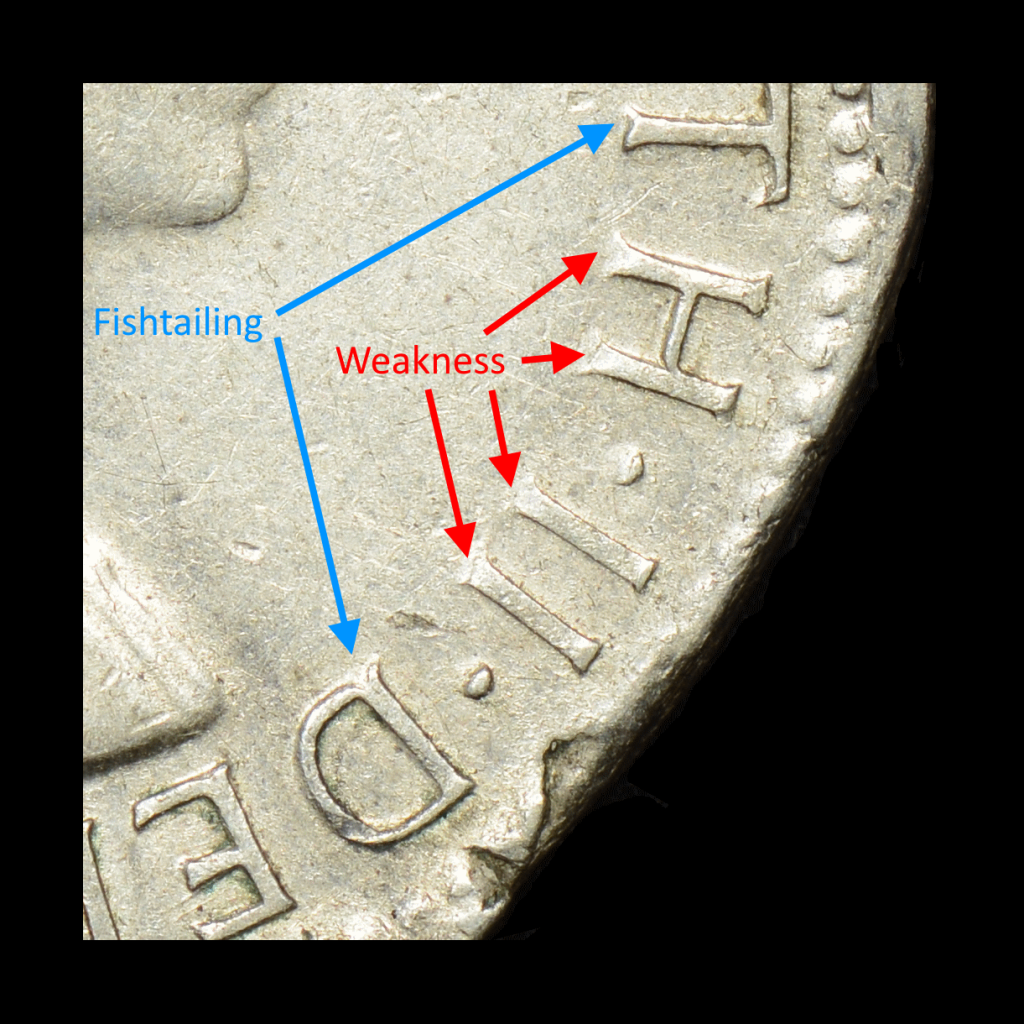

Condition is paramount for banknotes and our next task was to sort and grade them. We were hoping this would give us some idea of when the notes were put in the tin. Figure 3 plots the condition of the notes of each signatory pair, the data normalised to allow easy comparison. It can be seen that 40% of the newer Coombs / Wilson 10/- notes in the hoard grade Very Fine or better, while the oldest Sheehan / McFarlane notes are low grade, being Very Good at best. Given the relatively quick rate at which paper banknotes degrade in circulation, this suggests to us that the notes were removed from circulation not long after Coombs / Wilson 10/- (R-15) notes were first issued in 1952.

Figure 3 – Note Grade by Signatories (Normalised)

Star Notes

The first question we are always asked by anyone when they’ve found out that we have purchased a large group of banknotes is “Are there any star notes?” Australian pre-decimal star notes, or star replacement notes were printed with their own serial prefixes separate from normal notes. A star note was identified with a five-digit serial, and then a star or asterisk to the right of the serial. They were designed to replace damaged or misprinted notes in the production process. This way the note printing authorities could ensure that the correct number of notes was in each production bundle.

In Australia star notes were first issued on banknotes with the Armitage / McFarlane signatories and it is believed only for the last year or so of the print run. This makes them some of the harder to find star notes of the pre-decimal series.

Of course, we love checking hoards of banknotes for star notes as much as anyone, and we were pleased (as was the customer) that the hoard of 219 banknotes netted five star notes. Details of the five notes are shown in Table 2.

| Signatories |

First Issued |

Ref. |

Serial |

Grade |

| Armitage / McFarlane |

1942 |

R-13s |

G/64 00172* |

aFine |

| Armitage / McFarlane |

1942 |

R-13sL |

G/95 73269* |

Fine |

| Coombs / Watt |

1949 |

R-14s |

G/99 68223* |

VG |

| Coombs / Watt |

1949 |

R-14s |

A/1 64660* |

gVF |

| Coombs / Wilson |

1952 |

R-15s |

A/4 85027* |

gVF |

Table 2 – Star Notes

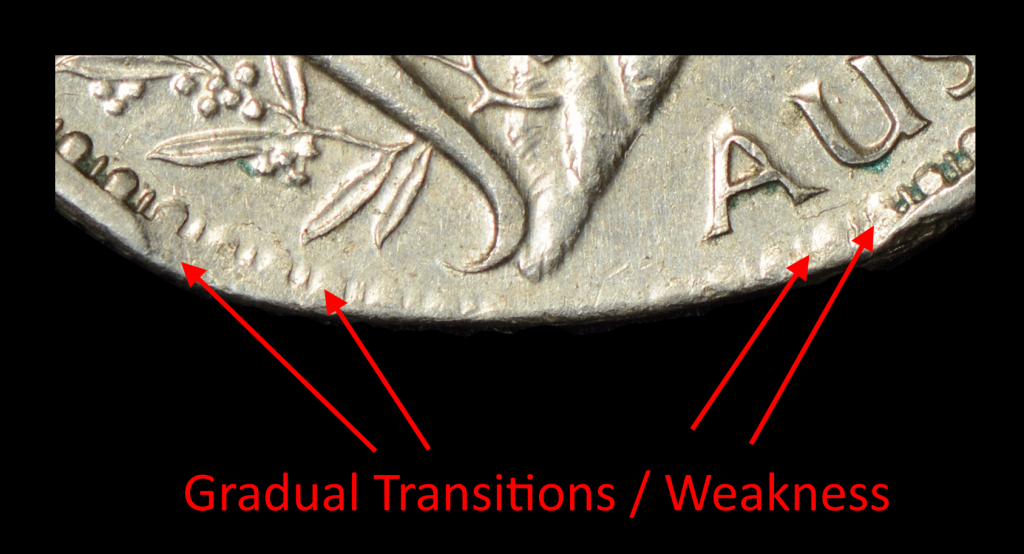

Figure 4 shows the better of the two Armitage / McFarlane star notes. This note also happens to be the last star note prefix issued for that signatory pair.

Figure 4. Armitage / MacFarlane Ten Shilling Star Note from the hoard.

Dating the Hoard

It’s always an interesting exercise to try to determine when a hoard was stored. In the case of this hoard, it must date to 1952 or later because the R-15 Coombs / Wilson notes were first issued in that year. Interestingly the group contained no 10/- notes issued under Queen Elizabeth so it’s reasonable to date it between 1952 and 1954. If we consider the silver coins that were also part of the hoard none of those date after 1946. Additionally, in some of the bags of coins there were scraps of paper with two sets of handwriting, one early notation in fountain pen confirming the number of coins and face value in a bag, and a check calculation in ball point pen that was dated in April 1974.

What about the baby formula tins that housed the hoard? A search of the wonderful website Trove (trove.nla.gov.au) quickly turned up very similar tins in advertisements from the 1940’s. Figure 5 shows just such an example, as found in the 19th of July 1945 edition of the Evening Advocate in Innisfail, Queensland (image courtesy Trove).

Given all the evidence, we’ll put a tentative date on the hoard in the mid-1950’s, say 1954, which is before QE2 notes were available and might explain why such a high percentage of the Coombs / Wilson R-15 notes were in better condition.

219 Ten Shilling Notes in the mid-1950s

It’s hard to wrap up this article without examining what the real value of 219 ten bob notes was in the mid-1950s. The notes add up to a face value of £109/10. The Year Book Australia, 19541 lists the average weekly pay for an adult male in 1952 as £13/18/2. Our tin of notes was therefore, almost exactly 8 weeks of an average adult male’s pay, which in today’s dollars2 would equate to almost $16,000.

Figure 5. Contemporary advertisement for Lactogen.

Why would the cash have been hoarded? For a reader in 2024, it’s not too difficult to understand with our media littered with references of the public distrusting banks and hoarding cash

6,7. In fact, the Reserve Bank of Australia recently said that “Banknotes that are hoarded – that is, held, either domestically or overseas, as a store-of-value, for emergency liquidity or for other such purposes.”

4 and goes on to say that “Hoarding, both domestically and internationally, is the most significant component of banknote demand. Hoarding is usually done for store-of-wealth or precautionary motives.”

4

Reports like this tempt us to think that cash hoarding is a new thing, but of course, it is not. The person (or people) who hoarded our 219 banknotes were the product of the Great Depression (1929-1939) and then World War II (1939-1945). An almost sixteen-year period of financial and personal hardship for billions of people worldwide when hoarding of cash and other valuables was commonplace.

The problem became so bad in some countries that their governments passed laws against hoarding with the US Treasury saying in 1933: “No banking institution shall permit any withdrawal by any person when such institution, acting in good faith, shall deem that the withdrawal is intended for hoarding.”5.

Conclusions

The authors consider this to be a purchase of a lifetime as it seems unlikely that we’ll ever see a hoard of this size in our shop again. We will document the hoard to the best of our ability and this article forms part of that effort. When the notes are sold, we will also ensure that some form of provenance is also supplied with them so that future owners know of their origins.

Mark Nemtsas and Kathryn Harris own and run ‘The Purple Penny’ coin shop in Adelaide and are passionate about error coins.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Year Book Australia, 1954, 1 January 1954, https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/1301.01954?OpenDocument [Accessed 24 February 2024]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Average Weekly Earnings, Australia, 22 February 2024, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/earnings-and-working-conditions/average-weekly-earnings-australia/nov-2023 [Accessed 24 February 2024]

- Pitt, Michael : Renniks Australian Coin & Banknote Values. NSW, 2023. 31st ed. Print.

- Elkington, Patrick. Guttman, Rochelle. Reserve Bank of Australia, Understanding the Post-pandemic Demand for Australia’s Banknotes, 22 January 2024, https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2024/jan/understanding-the-post-pandemic-demand-for-australias-banknotes.html [Accessed 25 February 2024]

- Silber, William. Why Did FDR’s Bank Holiday Succeed? FRBNY Financial Policy Review, July 2009. ttps://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/epr/09v15n1/0907silb.pdf [Accessed 25 February 2024]

- Rochelle Guttmann, Charissa Pavlik, Benjamin Ung and Gary Wang, Cash Demand during COVID-19, March 2021. https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2021/mar/pdf/cash-demand-during-covid-19.pdf [Accessed 29 March 2024]

- Nassim Khadem, Australians are hoarding more banknotes but how far away is a cashless society in a digital world? https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-01-05/australians-hoarding-banknotes-but-using-less-cash-to-transact/101777190 [Accessed 29 March 2024]

Appendix 1 – List of Notes in Hoard

The Milk Tin Hoard - List of Notes

| 1939 |

E/57 854646 |

Sheehan & McFarlane |

| 1939 |

F/14 145659 |

Sheehan & McFarlane |

| 1939 |

F/19 780136 |

Sheehan & McFarlane |

| 1939 |

F/19 846499 |

Sheehan & McFarlane |

| 1939 |

F/19 867474 |

Sheehan & McFarlane |

| 1939 |

F/19 928044 |

Sheehan & McFarlane |

| 1939 |

F/20 064134 |

Sheehan & McFarlane |

| 1939 |

F/9 262679 |

Sheehan & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/31 288698 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/31 512 558 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/31 634206 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/31 720263 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/36 339083 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/41 427122 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/41 461986 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/41 464394 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/41 536457 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/41 664660 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/41 688991 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/41 689288 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/41 815277 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/41 827227 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/43 817268 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/47 387207 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/47 415408 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/47 425784 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/47 527364 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/47 612523 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/53 081428 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/57 155080 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/57 290883 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/57 314294 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/57 440282 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/66 434178 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/66 444593 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/66 579993 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/66 633209 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/66 653913 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/66 701564 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/66 722658 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/66 723843 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/66 966079 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/66 985938 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/67 000259 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/69 898640 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/70 050917 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/76 298109 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/78 021861 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/78 166436 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/79 692194 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/79 700833 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/79 703659 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/79 884772 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/79 986474 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/80 009720 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/80 208120 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/80 523695 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/80 580457 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/80 632718 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/80 639477 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/80 642536 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/88 431040 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/95 005834 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/95 179427 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/95 311913 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/95 385813 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/95 540150 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/95 563184 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/95 620659 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/95 686894 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

F/95 708865 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/1 209413 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/18 565793 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/20 584828 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/21 355755 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/21 425958 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/21 472925 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/21 518778 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/21 529319 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/21 741733 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/24 290678 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/28 174481 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/28 183662 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/28 537437 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/28 662710 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/28 665975 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/28 745220 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/28 751899 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/36 109130 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/36 187383 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/36 249276 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/36 453770 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/36 486667 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/36 487327 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/36 695436 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/36 737780 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/36 830641 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/36 894860 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/49 742241 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/49 752006 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/49 799164 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/49 842997 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/49 956599 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/50 051025 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/50 230084 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/50 248975 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/50 266077 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/50 295962 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/50 333476 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/6 511982 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/64 925289 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/64 981326 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/64 995261 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/65 00172* |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/65 027963 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/65 075459 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/65 231751 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/65 421406 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/65 476722 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/7 127288 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/7 139296 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/7 203671 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/7 340993 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/7 382139 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/7 388829 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/7 400137 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/7 535045 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/7 667058 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/7 723846 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/7 835152 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/74 002477 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/74 074193 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/74 190637 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/74 309139 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/74 373685 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/74 519944 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/74 662504 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/74 690621 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/74 698462 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/82 605239 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/82 919345 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/82 961206 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/83 304647 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/9 403232 |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1942 |

G/95 73269* |

Armitage & McFarlane |

| 1949 |

A/1 64608* |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/10 087473 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/22 074923 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/22 094603 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/22 187436 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/22 373396 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/22 396695 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/22 483139 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/22 498942 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/22 599836 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/22 806306 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/26 454419 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 138429 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 267696 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 324625 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 325410 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 330726 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 343601 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 445391 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 516057 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 591742 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 766464 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 835480 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 885518 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/35 963339 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/44 766106 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/50 109336 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/51 208909 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/51 654237 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/51 663088 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/63 525525 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/63 531657 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/63 832282 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/63 878359 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/63 901196 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/64 021938 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/64 022563 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/64 078580 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/64 145260 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/69 724233 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/74 888351 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/74 990941 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

A/75 504446 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1949 |

A/75 578872 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1949 |

A/75 583920 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1949 |

G/87 156367 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

G/92 457771 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

G/94 160265 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

G/94 201929 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

G/94 452300 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

G/94 676577 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

G/94 683085 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

G/94 683258 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

G/94 721343 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

G/94 832253 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

G/94 965286 |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1949 |

G/99 68223* |

Coombs & Watt |

| 1952 |

A/4 85027* |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/82 445028 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/83 855762 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/83 959277 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/83 987317 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/84 065194 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/84 279663 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/84 515630 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/84521003 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/93 682141 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/93 706836 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/93 974844 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/94 203168 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

A/94 253951 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

B/3 010392 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

B/3 203341 |

Coombs & Wilson |

| 1952 |

B/3 352281 |

Coombs & Wilson |